When you call a festival “Movement,” you certainly expect there to be quite a bit of the title at the event itself. But at the tenth anniversary of Detroit’s most celebrated music festival, what most comes to mind — and what is often forgotten in the time between subsequent editions — is how much “movement” there is in the lead-up to the actual event. Days and days of planning, mad-dash rushes at the last minute for supplies, frenzied calls and e-mails searching and begging for tickets to after-parties, requests to get on lists — a frantic sort of pace sets in the mind and body before you even step into Hart Plaza.

But then you get inside the gates, and despite all the colorful garb and the buzz of activity, in spite of all the stages pounding and blasting all sorts of beats, a calm washes over you. You’ve made it. You are in Movement, and Movement is in you.

Movement is more than just a festival. It encompasses more than just the artists, or the six stages, or the after-parties, or the vendors, or the day-glo fashion, or anything you might associate with the event itself. Movement isn’t a feeling, or a sensation, or a vibe. Movement is tautological, in that the word itself is what it is. Movement is a movement, and it’s been going strong for ten years now. And that Movement lasts beyond any single day. If you’ve ever been, you know that you carry it within you. But for now, let’s start with day one of Movement 2016.

All photos by Nick Kassab

The first major set of the day came from Kyle Hall, a young local DJ and producer whose rise has paralleled the ascendance and emergence of a larger “New Detroit” narrative. His sound pulls not only from the storied history of the city’s own electronic music legacy, but from a grabbag of genres miles away from techno’s mechanical grind. French touch phaser effects and New York boogie bass are as likely to pop up as hi-hats or 808s. Hall’s latest album, From Joy, plants roots in the Motor City but casts a wide net across dance styles, with an infectious energy that recalls the anything-goes mentality of The Electrifying Mojo’s formative years.

This joie de vivre was in plain view both on stage and throughout the crowd during Hall’s set, even if you couldn’t hear a note of music. But paired with the bouncy, woodblock rhythms, breathy vocal samples, and ringing whistles, the projections on screen took on a new meaning. Multi-colored prisms, a futuristic cityscape, and Tron-like cubes and spheres all seemed to reflect the transformation that’s been happening around town lately, and the upbeat, jovial attendees couldn’t help but catch that feeling. As one of the samples kept singing “sunshine of my life,” there was a sense that this was the dawning of a new day, and what better time than on the tenth anniversary of Movement?

The pleasure continued over at the Made in Detroit Stage, where Matthew Dear took a step out of the shadows of his normally murky, jet-black music to also make way for the sun. On a day as sweltering as this, even a wraith-like producer such as Dear couldn’t help but step out into the light. Where once his oscillating rhythms might spiral down into the depths of a K-hole, his set at Movement introduced tropical house beats into the mix.

Of course, Dear would never go full-on Balearic, and this was evident in the way he threw in sinister-sounding synths that cut through the aural foliage like buzzsaws. Dear was transporting the crowd on an Audion journey, and the throb of the beat — coupled with the high afternoon temperatures — made the stage pulsate like a jungle on Jefferson. But every once in a while, Dear would release a sudden drop that felt like a welcome monsoon after the long stretches of slow-burning, smoldering builds. Once again, a sample said it best: “You take my breath away.”

The gradual fade-in is unusual for a mainstage act, but not when your name is Seth Troxler. After all, this is a man who will soon be climbing Mount Kilimanjaro. Like that Herculean trek, Troxler’s music scales great heights one step at a time, and it rewards close attention. The rhythms build, the vocals ebb, the beat flows, and the senses are overtaken one by one. Troxler’s demeanor onstage is one of restrained ease, of assured poise, of “Relax, I got this.”

You feel so comfortable in Troxler’s presence that you stop to talk to your friends, and when you turn back to the music, the sound has gone from mild-mannered to livewire without you knowing what hit you. That’s when you know why a seemingly unassuming producer like Troxler gets chosen for the big leagues, and that’s also how you know he’s going to conquer a Tanzanian massif. He’s elevated you; you’ve hit a peak. Can we get much higher?

It turns out we can. And to do so, we get back to basics. Stacey Pullen is one of the icons of Detroit techno’s second wave, and he knows that no amount of bells and whistles will do the trick if you don’t have the right supporting structure. Pullen’s set attracted a sizable crowd, and that’s no small feat, given the two-hour running time and the open-sun setting of the performance. What, exactly, was pulling fest-goers away from the shade and over to the stage?

On the surface, you’d think you’re just hearing four-on-the-floor rhythms accented by kick drums and Rolands, but scratch a little deeper or lean in a little closer, and what you’re really listening to is a master at work. Pullen knows how to tease and release, controlling tension and excitement by playing with the simplest of compositional tools: dynamics, tempo, melody. And he’s also one of the poster children for the “It’s not just techno!” camp, subtly incorporating touches of house and garage into the gears and paving the way for future producers who expanded the boundaries of Detroit’s sound.

Skirting the boundaries of that sound were quite literally, Borderland, otherwise known as Juan Atkins and Moritz von Oswald, who played sequences from their latest collaborative album in a freely structured improvised session. Atkins, known variously as “The Originator” or “the godfather of techno,” teamed up with von Oswald, one of the pioneers of dub techno, for this no-frills set that was like a striptease of the senses. But for as much as the two icons took away, they also brought a lot to the picture.

Atkins and von Oswald understand that sometimes to make something new, you’ve got to wipe the slate clean first. And so they delivered an early evening palate cleanser before the next course. Once the plates had been cleared, the two set out on their mission, and it was one of almost ancient historical precedent. Their process was that of accretion, of accrual. Sounds were built up like layers, until the music formed a pyramid. If you turned and faced away, you’d see the steps of the amphitheatre, and it was the music made flesh: a Borderland. Turn back around and face the stage, with its draped tarps and blank scrim, and the boundaries would dissolve. Atkins and von Oswald weren’t just musicians; they were magicians.

Another kind of magic was happening at the Opportunity Detroit Stage: electronic music without the “traditional” electronic equipment? It seems impossible — or at least anachronistic — in this day and age. Or maybe it’s not, given the zeitgeist’s fascination with all things handcrafted and vintage. But don’t call Ectomorph anything as gauche as “retromorph.” The Detroit act’s use of analog predates our era’s longing for something real.

Ectomorph were ahead of their time and still are. To listen to their songs is not to feel like you’re traveling in some wayback machine, but to zoom forward through a wormhole of possibilities. Their music resembles a rotating double helix, with individual notes taking on the function of chromosomes, like units of sound denoting compositional form. It lends itself well to ad hoc coordinated dance routines, even as the gyrations of the music spin on an axis that obey no natural law.

Law and order would appear to go by the wayside when you step into the deep recesses of the Underground Stage, where British musician Paul Rose was performing a set. But as his moniker Scuba implies, the subterranean terrain of this area hasn’t descended into chaos, but rather the code it abides by is simply submerged. Like his music, which applies an experimental bent to post-dubstep’s wobble, the Underground Stage requires a certain constitution, special equipment of the soul. There’s a depth charge, and if you come up too fast for air, you’ll get the bends.

But worry not if that happens, because Carl Craig will straighten you out. One of the best-known legends of Detroit techno’s second wave, Craig’s set at the Made in Detroit Stage turned the city into a dancefloor in more ways than one. He welded the many strands of Motown’s sound into shards of a kinetic audio sculpture, a hanging mobile with New Jack Swing. On screen there was a disco ball atop the skyline, and it was as if you could make out a facsimile of the famous AT&T symbol through the haze. There was a billboard, too, like a projection of our desires: and what were they exactly? Detroit Love.

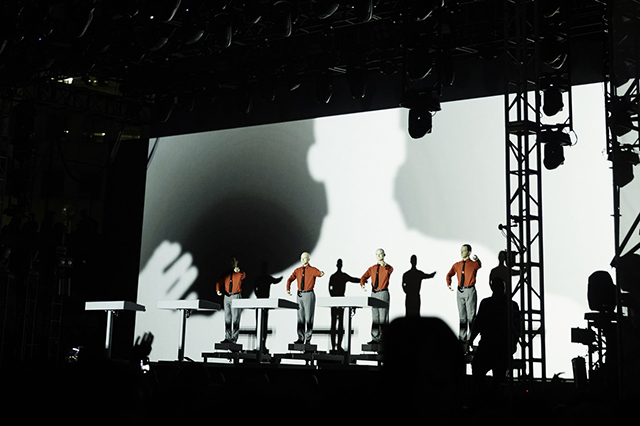

How did we get here to begin with? Where did the love come from? The answer to that is an unlikely place and even more unlikely people: Düsseldorf and Kraftwerk. The German band, whose driving, repetitive, motorik rhythms and use of mostly synthetic instrumentation is credited with kicking off electronic dance music as we know it today, were in attendance for a rare live performance and their first set at Movement.

Festival attendees were handed special 3-D glasses prior to the show as the group would be accompanied by visuals for such classics as “Trans-Europe Express” and “The Robots.” As night descended on the sky and the lights came up on stage, four figures appeared on the stage, going through a repertoire that was as familiar as it was futuristic, as human as it was alien, as of this earth as it was out of this world. Kraftwerk may hail from lands Teutonic, but tonight they belonged to Detroit.

Over at the Red Bull Music Academy Stage, two acts closed out the festival that straddle the line between the indie world, the electronic sphere, and the dance arena. First, English musician Kieran Hebdan, aka Four Tet, proved that you can make jungle music that isn’t actually jungle proper. His set dabbled in a surfeit of styles — loping hip-hop breakbeats, homespun “folktronica,” mechanical techno, free jazz drumming, grime SFX — that hovered around the equator. Even though the temps had cooled down a bit, Hebdan kept things hot and heavy, which the crowd responded to with enthusiasm and cheers.

It was the perfect lead-in for the final act of the night, Canadian musician Dan Snaith, who performs as Caribou. Although Snaith has a house-oriented project known as Daphni, Caribou has moved away from his ’60s-inflected psych-pop and toward the dance end of the spectrum over the last decade. His set at Movement borrowed heavily from his last two albums, Swim and Our Love. With extended versions of such jams as “Found Out” and “Your Love Will Set You Free” pouring over the crowd, hitting pleasure centers and firing off synapses at just the right moments, it was a fitting conclusion to a first day of Movement 2016.

See more from Movement Electronic Music Festival 2016 below:

Visit Detroit Music Magazine for more photos and recaps throughout Movement weekend. Discover more Detroit Music Magazine coverage on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat at @detroitmusicmag.