In the world of Jeff Mills, Space Is the Place. That phrase comes from a 1974 film directed by John Coney, written by Joshua Smith and Sun Ra, and featuring the latter jazz musician. Although Mills is most readily associated with the second wave of Detroit techno, the many threads of his work and career can be teased out from this little-known movie: an ongoing obsession with science fiction, the use of Afrofuturist motifs, a deep belief in the power of extramusical content and symbolism, and even his flirtation with cinema itself. Moreover, just as Sun Ra had his Arkestra, so too, has Mills sought out collaborations with orchestras and other classical musicians in recent years.

But of course, the Jeff Mills that most people know is “The Wizard,” whose magic lies in his unparalleled DJ’ing abilities and experimental production skills. As the founder of Underground Resistance, a techno collective he formed with “Mad” Mike Banks in the late 1980s, Mills brought a political element to the genre, which had hitherto been detached from subject matter and only interested in formal concerns. Later, the artist would start his own label, Axis Records, before embarking on creating increasingly complex works throughout the world.

Jeff Mills’ latest project is a sequel to his 2004 piece, Exhibitionist, which sought to demystify the art of DJ’ing, while at the same time reveal the intricacy of its craft. In the process, it debunked many of the notions surrounding dance music’s validity as a genre. The follow-up, which comprises three parts, takes advantage of new technologies to go even deeper into capturing the creation and production of electronic music, and it’s as adventurous as any of Mills’ endeavors.

Detroit Music Magazine spoke with Jeff Mills around the release of part two of Exhibitionist 2. His passion was evident throughout the conversation, as if his mind were set to warp drive and the rest of him — and us — were struggling to play catch up. If space is indeed the place, then Jeff Mills is out there mapping the final frontiers.

Exhibitionist 2 is a magnum opus, and you have one more part coming out. How does Exhibitionist 2 relate to the first Exhibitionist, and what was the impetus behind revisiting the project?

With the second release, what I had intended to do was to further explain more about the art form or the artistry of the DJ – more aspects about what it takes to actually program music for people. On this one, we went more to music production, which is something we didn’t do on the first one. And overall, I just wanted to show the process works – from what one thinks, to what one does, to eventually what one person hears and what he experiences – and how that information can sometimes be taken back for modifying music once again. And so I thought it would be most important to kind of try to capture the mindset or to try and get some insight to explain the intention of what a DJ is trying to do with the music.

So there is where it’s different from the first one. And then the idea itself really, I guess I was not as aware of it when I made the first one, but it became more apparent that by allowing the viewer to be able to see more and possibly understand more about the art form, perhaps – maybe – somehow, it would be easier to see the value of why it’s so unique and why it’s something that we shouldn’t always take for granted, that it’s something that any and every one can do, that there is a craft to all this, that there is a way to learn it in a way that you can really use it to say things that are quite difficult to say with words.

I appreciate you talking about that, because it seems that in the age of the Internet and with the democratizing of music production, many people believe – as you said – that anyone can “be a DJ” or “be an electronic music producer,” but your work on the Exhibitionist series reveals that there’s a way to actually craft music using these tools and software.

Yeah, I suppose you could say the same thing about playing a guitar. Any and every one can probably learn how to play a guitar, but in order to be able to do this you have to understand what it is to actually play. You have to learn notes, you have to use it in a way to be able to manipulate strings, to make chords, to do things like that. It’s the same thing with DJ’ing. There’s much more than just mixing two tracks together, and the better that you get at that, the more complex you can make your compositions. You can use three or four turntables instead of two. If you can integrate drum machines and other instruments into your DJ set, you can express yourself more. So I mean, yeah, everyone can do it, but not everyone can learn it to the extent where you can really begin to modify and change things in real time.

And so I thought that, you know, by using drum machines more, we can highlight in this DVD the idea that – yes, programming really is a large part of electronic music – but it doesn’t always have to be that way, that sometimes picking up that equipment to be able to do things spur-of-the-moment, or as it’s happening, can also work and create a very unique presentation that, in my opinion, is even more special, because – like I said before – you’re giving the listener and the audience something that will never be again, you know, that you’re not able to do again because you just made it up. And I think that for a long time that’s been kind of missing from electronic music – that naturally things are going to happen by chance because of the way that technology is allowing us to be able to pre-program, and pre-prepare. And also the way that musicians are using it as well, it’s kind of steamrolled the idea of spontaneity and improvisation that should really be in our art form.

One of the elements in Exhibitionist 2 is a very human element. Another artist that you brought on to perform was Detroit drummer Skeeto Valdez. How did that collaboration happen? Did you work with him before, and how was it working with him on Exhibitionist 2?

Well, I have to go back to my first idea. The first Exhibitionist wasn’t [supposed] to have Lawrence and Lenny Burden from Octave One. My initial idea was to have DJ Rolando – where the camera would pan to a different DJ set, where he was much more physical with the records in a different way, and then pan back to me, and so on. But he wasn’t available, so I had to do my second idea, which was Lawrence and Lenny, and they just happened to be in Detroit at the time. I asked them if they could, you know, create a live performance, and the camera would pan here, and that’s all. Well, you know, why doesn’t it pan, like a second time, to something else? But to make a long story short, we only made that one pan.

But for the second [Exhibitionist], I kind of had a similar idea, that it would pan from me to a drummer and then pan to a live singer. We would hear all this, you know, me layered up under the drum machine, layered up under the vocalist. Eventually, it turned out to be just Skeeto and I. To find him, what we did, we just looked around Detroit, we tried to find the best drummer that we could find in the Detroit area. Lots of people referred us to Skeeto, so we approached him and asked if he would be interested in this idea, and he luckily agreed to do it. We didn’t have much time to record it, so he did not warm up at all, you know. He had another gig to go to after this recording, so he just took the drum machine, and I explained to him what was going to happen. I started the DJ set, the camera kind of panned over, and he did his thing without prepping at all, and we just did it in one take. And it came out great.

I’m glad to hear that it worked out in one take. You mentioned scouring Detroit for drummers. Detroit’s where you got your start, but you’ve relocated a couple times. You’re in France right now, and you’re headed to Japan shortly. You’re an international presence. How do you see your roots in Detroit connecting with the work you do today, and what is your connection to the city these days?

Detroit, as long as I’ve ever known, produces a certain type of musician. Like I knew this back in high school, back in the ‘70s. It was always kind of common knowledge if you were a musician, if you were young, you kind of knew that Detroit had the type of climate that produces a certain type of musician who’s typically well-rounded, that can play just about anything – very adaptable to just about any type of situation. Maybe that comes from Motown, I don’t know. Maybe that’s something that Berry Gordy and those guys sort of created, that type of atmosphere.

So I always kind of knew, say for instance, that if I met a person who was originally from Detroit and said he’s a musician, I’d know that he probably has a certain way or a similar school in which he was taught to play. And that helps greatly, actually. I first recognized this when I first left Detroit and I moved to New York. I began to realize how musically trained I was compared to other people there – not that I knew how to do certain things, but that I had a much wider knowledge of music, and that I guess would be the accumulation of growing up listening to [Electrifying] Mojo, or going to rock concerts and hip-hop shows, and [watching] TV, and [listening to] soul and funk. And I was around people who didn’t have that depth in terms of music – disco and all those types of things. So it kind of prepares you, being able to understand things in a certain way.

I’ve always known that Detroit creates a certain way that we listen to music. We tend to listen to it in a more serious way, or we want to extract the message out of it first, more than anything. Marvin Gaye sounds great, but you’re really listening to what he’s saying. I think when you’ve grown up in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, I think you really put a lot of value into what’s in the composition. I think that really carried over into Detroit techno, as well.

So I think that we tend to approach music in a much more serious way, because we know it’s a way of communicating and extending one’s voice or one’s ideas. I’ve never known artists from Detroit to make fun of music or to present it in a silly way, and I wasn’t really largely exposed to that until I left Detroit, when I began to be around other producers and other things. They didn’t take it quite as seriously as we do [in Detroit].

You touched on a few things that relate to my next question. You talked about how there’s a culture of musical training in Detroit and that it extends to this broad range of genres. You also talked about communicating some form of content or idea through your music, and I see that all coming together in the last fifteen years in your work with classical musicians and ensembles. Do you have any classical training? How did you find yourself in that world?

No, not at all. I had to really think about how I would be able to communicate to someone who is classically trained, and I realized that we have to get beyond the fact that this is electronic music and that’s classical. So I thought maybe it makes more sense to just focus on what concept these tracks were about. Then it would be easier to communicate and to work with other musicians and arrangers and conductors if I could explain why the music was made in the first place.

Luckily, I had a lot of music that was released, but it wasn’t the type of composition that was so easy for DJs to play or people to really consider them as pure techno tracks. But I had released quite a few of them in the early part of my career, and it was enough to be able to present to an arranger, and I explained to him why these tracks were made and what these tracks meant and what the sounds were trying to translate – basically, how the composition was actually working, what the scenario was.

From being able to do that, the arranger could then assign what sounds would be assignable to what musician in the orchestra. So if a track is the accumulation of a conversation between two things, then the arranger would know that he needs to break the orchestra up into two parts, or the string arrangement up into two parts. So that was the way I was able to communicate that in 2005, to explain how these techno tracks could be translated for an orchestra.

So far, I’ve just explained the scenario for myself. But we have to imagine how many other artists in electronic music have released tracks like this, or like those, that could be translated for an orchestra, and how much more potential we would be able to produce in these type of performances and collaborations. If someone like Joey Beltran sat down and got all his compositions that were more structured and presented those to an orchestra, I would imagine it would be a lot of activity if producers began to do that.

So that’s the way it happened. That’s the way I’ve been lucky enough to be able to communicate, and it seems to work really well because on the classical side, they are trained by works: by Mozart and Beethoven, and things like that. They know what those compositions meant. So if something is about space or the stars, then they know that Stravinsky has made something like that, and they can relate to it.

You’re a pioneer in that sense. I saw Derrick May perform many of his compositions with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra this summer, including Strings of Life. But something you mentioned that’s really become part of your aesthetic is this sci-fi approach to music. A lot of the concepts you explore have to do with time or light or space – these grand concepts of physics and the convergence between what is possible and what is actually happening. We see that in the collaborative work you did with classical pianist Mikhail Rudy, and on the work based on 2001: A Space Odyssey, which also brings me to your fascination with film. You’ve worked on scores for Metropolis and other great films. What draws you to film, and would it be correct to say you have a predilection for science fiction?

Yeah, it’s something that I kind of grew up with a lot, starting when I was young with cartoons, and then with comics, and then science fiction films and TV shows. I have an older brother who was into space science. And as long as I can remember, this subject has always been there, you know, and not just with me, but with my neighbor and with the kids I would play with. They had older brothers, and they were all into the same thing. And so you kind of grew up with it.

It could be that that’s what attracted me even more to it in the ‘80s, when I was on the radio in Detroit and was playing mostly hip-hop and I really began to navigate more toward Detroit techno. Well for one, because it was from Detroit, but the subject matter that they were using in order to be able to create the music I thought was really interesting and very new and very reflective of the time in which we sat in. We were in the mid-80s, fifteen years before the turn of the century, caught up in the swirl of popular culture and anticipation of what the world would be like after the year 2000. And so I guess I really wanted to be closer to a type of genre that was kind of reflective of that.

But it’s always been there, though, for as long as I can remember. And I always was quite fond of it, whenever it was related to music, and not just Detroit techno and Juan Atkins. There were a lot of other things that kind of reinforced this science fiction. I mean even the show of [Electrifying] Mojo was fiction, you know? And the idea of the way he formatted his show was a trip to somewhere else. And movies when you’re a kid, and Star Wars, they were a trip to somewhere else – very deep and very far away.

So the interest was always there, but I guess I didn’t really begin to get into it until about the year 2000, I think. When I guess I was convinced that I had done a certain amount of things with dance music, then I felt that I could branch off and explore more experimental subjects with the music. That’s when things started to take a turn.

One of your experimental bents has led you to the art world. You recently completed a residency at the Louvre, and shot a film in the Egyptian wing. What was the inspiration behind this work? What drew you to that area of the museum?

When I was given the residency, when I first got the invitation – that was one of the main things that I really wanted to accomplish, which was to create something or to do something with the Egyptian wing because it’s so large. I don’t know, something like 10,000 artifacts, three floors of works. What convinced me the most was that I could not remember anything in my past where I’ve ever known of anyone doing anything in that museum with these types of works like this.

I thought that it would connect with many people in America, specifically Afro-Americans, or because the fact that America is still pretty much a very religious country. The idea of what life means and what happens after death is something I thought would also resonate with people back home if they were to ever see it or experience it. I mean, I’m not a very religious person, but I studied Egyptology extensively in order to be able to produce this.

What I ended up actually making was a film – a full-length feature film – about an hour in length, and what it depicts is how the gods would fit into the society of Ancient Egypt – what they would mean and how they would govern their world, I suppose. I had never done this before. I had never made a film before. So when I thought I would have a reasonably good chance, that if I laid everything out on paper, if I did everything in diagrams, storyboarded everything, and if I could find the right people to help me do it, then it might be possible.

So I literally planned everything on paper. I knew that I wanted to have three dancers to dance through the entire exhibition, as if they’re dancing through life. They descend to Earth from the heavens, from the stars – the Star System of Orion – and then to Earth. Using the staircase in the museum that’s right in front of the exhibition, they would descend down that staircase to the main floor, which would actually be Earth, and they would begin their walk through three galleries, which would symbolize life, and then they would descend down another staircase, which would represent that they would be dying, and then at the end of the staircase, they would then die. Just by coincidence, at the end of that staircase is the tomb and sarcophagus of Osiris, and Osiris is the god of reincarnation.

So that’s the main structure of the film. Certain parts of the film would cut to parts of the exhibition where the dancers would play out different types of routines amongst themselves. It took about a year to plan the whole thing. I was looking for certain dancers, a certain look. They all had to be over six feet tall. They had to be of a certain character. There were costumes and basically, you know, a movie set. And then because it’s a very old museum, and nothing like this has been done before, there were a few things I had to kind of figure out, like how we would apply sound to the film set without having to run cables all over the museum. So I had to create a wireless sound system that could move with the dancers as they were walking through the museum.

We shot everything with natural lighting, so only the light that’s coming through the windows of the museum [was used]. Things had to be shot almost in real time, because the light was moving throughout and over the museum. We couldn’t do three or four takes. It had to be shot almost in one take. So that reflected in the rehearsals and how much we rehearsed and then come in. I could go on and on, but we shot it in two days in a total of sixteen hours, and then the editing took a few weeks.

When we screened it, we made a special part at the end after they died. We did an afterlife segment – the time in between life and death. That played out on the stage following the film in front of a live audience, and at the end of that performance, the dancers die onstage. It was a pretty dramatic ending. Maybe I’ll have a chance to bring it to Detroit, if I’m ever invited, but it’s very interesting. And that was just one of the four weeks that I had to materialize within a year. I had a total of four shows. All of these things had to be organized within about twelve months. It was a lot of work.

It sounds like the finished product was pretty remarkable.

Yeah, considering I had no experience, and I could get a few people to help, but after a point, they weren’t able to help me. I mean I went to the museum many different times to measure the lighting, to get up on stage, to measure the acoustics, to measure the reflections – because in the museum everything’s in glass cases. How do I get the camera and everybody out of the way so that we don’t have these reflections in the glass cases? So I had to figure out what the movements of the cameras would be. Yeah, it was a lot. It was probably one of the most detailed projects I’ve ever done.

Well, I do hope we get to see it in Detroit. You’ve done film, you’ve been a DJ, you’ve been a producer, you’ve played on the radio, you’ve moved all over the world, and you travel extensively. What is next for Jeff Mills?

What I’m looking at and studying more is about – and I suppose it’s a form of curation – is being able to create certain types of atmospheres. I guess sometimes consisting of art, sometimes consisting of fashion, sometimes consisting of artifacts. At the beginning of this year, I tested a concept called “Weapons” in Tokyo. It was a show consisting of artifacts based on a very famous UFO sighting in Los Angeles in 1942: newspaper clippings, things that people were listening to during this strange event that happened. We rented a warehouse space in Tokyo and created an event that was really about an atmosphere that was kind of narrated with film noir – film from the 1940s. It was the accumulation of a few different things, and so we think that maybe that might be a direction I can go in more – sometimes small, sometimes large – but basically, yeah, we think that might be something to work with for the next couple of years.

Parts one and two of Exhibitionist 2 are out now and can be purchased here. Part three will be released in November 2015. Watch the trailer below:

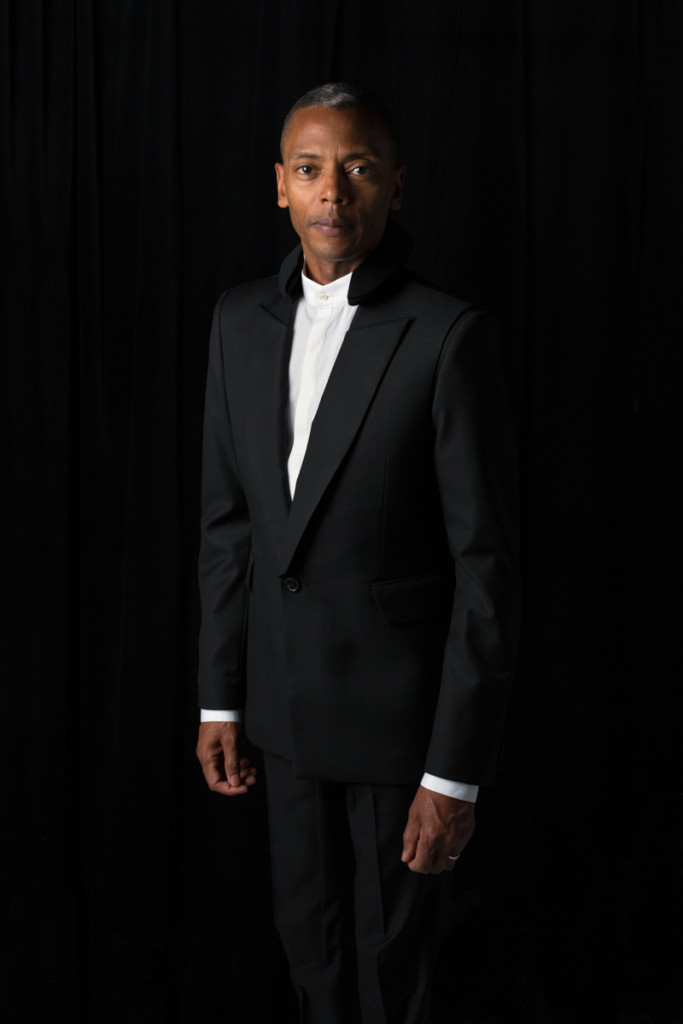

Photos courtesy of Axis Records.