Nestled between a vegetarian-friendly diner and a gourmet bagel shop on Michigan Avenue in Corktown — Detroit’s oldest, but also one of its hottest, neighborhood — PJ’s Lager House has long been known as a hangout spot for local bands such as The White Stripes and a destination for touring rock acts looking to play an intimate venue.

The Lager House is where I first saw Protomartyr, a Detroit-based quartet whose bracing mix of propulsive energy, introspective lyrics, and abject subject matter put them in the same league as post-punk barn-burners such as Wire or Iceage. But Protomartyr are another animal altogether, and no game of spot-the-influence can quite pin them down.

That night’s performance followed on the heels of their sophomore album, 2014’s Under Color of Official Right, and was an opening slot for fellow Detroiters Tyvek and Brooklyn’s Parquet Courts. In the time since that show, Protomartyr have seen their star rise like few local acts in recent memory. They released another full-length to considerable acclaim, The Agent Intellect, and have continued touring with nary a break.

Tonight, Protomartyr’s frontman Joe Casey is onstage once more at The Lager House, but this time it’s not where live acts typically play, he’s not singing, and he’s not joined by the rest of his band. Instead, he’s reading off questions as teams of bespectacled and bearded twenty- and thirtysomethings huddle together at tables, trying not to knock over their beers as they hastily scribble their guesses to his queries.

Tuesday is Trivia Night at PJ’s, which Joe Casey hosts regularly. Given his workaday demeanor, it’s a fitting gig for the otherwise musician; in fact, the whole situation feels very “Detroit.” None of the patrons seems particularly fazed by Casey’s presence, and his professorial garb is worlds away from anyone’s idea of how a rock star should dress. Despite Protomartyr’s success, the band remain down-to-earth, working-class people trying to make a go at it in a fucked up world.

Why does it shake? The body, the body, the body, the body, the body, the body…

One of the categories tonight is bodily fluids, which also seems prescient for Protomartyr. Their music often explores themes of physical decay, mental decline, and corporeal erosion. These are some tough questions, yet Casey is able to relay even puerile, joke-ready material about smegma with a deadpan delivery that would give Norm MacDonald a run for his money.

The most apposite category, however, is one devoted to David Bowie, who died two days earlier. Casey, an avowed fan of Bowie, might not seem to have much in common with the Thin White Duke (although in a past interview he’d jokingly referred to himself as “the Fat Short Dude”), but parallels can be drawn between The Agent Intellect and Bowie’s final album, Blackstar.

The use of theological personae, the fixation on mortality, the unabashed embrace of nihilism — these themes bind Bowie and Casey, even if sonically Protomartyr’s malaise is far from Ziggy’s mystery. And though the desperate and despairing characters who populate The Agent Intellect may not be Heroes, they are anything but losers. Call them anti-heroes. And isn’t that what a Blackstar is, anyway?

I spoke to Joe Casey after Trivia Night wrapped up, a week before Protomartyr were set to go back out on the second leg of a world tour. In a month marked by so many notable deaths in the music world — David Bowie, Lemmy, Glenn Frey — Casey’s words were a welcome, and unexpected, affirmation of life.

Your latest album, The Agent Intellect, hangs heavy with the weight of loss. Both the world of music and the world at large experienced another loss recently, and I have to put this question to you right away: What were your thoughts and feelings when you first heard that David Bowie died?

My very first thought was looking online and seeing people were still celebrating his birthday, and I couldn’t figure out why they were still talking about it until I realized he was dead. Right now, I’m amazed that he went out the way that he did. I mean, people knew that he was sick for a couple years, but his releasing the album, having kind of his final statement be so perfectly timed?

I saw somewhere online, just today, that I think people can get a do-over on the reviews for the last record, because it’s funny seeing some of these reviews: “Typical old man music!” “Oh you know, he’s always talking about old man problems!” “Ah, the music isn’t so good!” But now that they know it’s his final statement, a lot of them would probably like to go back and say, “Oh, it’s really profound!” So I think it’s really astute on his part.

It’s one of those things where I love David Bowie, and I love his music, and I’m just kind of processing how I’m seeing people online… I don’t know. It’s interesting. I’m surprised at the outpouring. I’m trying to think of who else in the rock ‘n’ roll pipes is still alive who that will happen to. I suppose when Bob Dylan dies there’ll be a lot of the same sort of outpouring. Or when Prince dies. Besides that, I can’t think of anybody else.

You lost your father not too long ago, and your mother is living with a terminal illness. When listening to The Agent Intellect, I couldn’t help but think that your parents were on your mind during the writing and recording process. Yet the album doesn’t just dwell on themes of mortality, death, or bereavement. It covers a lot of terrain, and you stated something similar about David Bowie’s final album, Blackstar. People had their hot takes on it — that it was “old man music” —but now they’re looking at it in a different light. What was your process in writing The Agent Intellect, and when you were recording it, how did it come together?

Well, just to go back a bit, with David Bowie the funny thing is that people are now looking for this, “Oh, he’s talking about death on his last record.” But you can’t avoid it, through his whole career, right off the bat, he was really talking about death and the impermanence of self. It’s kind of a heady topic, but he’d been doing that since album one. With me, I don’t know if I’m a morbid fellow, but all three of our records so far have kind of talked about that.

I think more so with this new one, The Agent Intellect, it’s about dealing with Mom. Mom is still my mom, still alive. There’s good days and bad days, but she’s fundamentally a different person than she was ten years ago, five years ago. It’s kind of been a slow decline, and you never know how long it’s going to take. But just kind of dealing with that, seeing how you’re not ever really yourself, how you lose that so quickly — who you are — to me, that’s kind of a thing that’s worth talking about, especially in songs and music. Just by singing a song or writing lyrics, you are fictionalizing something. You can take your diary and put it right to a song. The fact that you’re singing it already makes it different.

So there was enough on this new album to make that a central theme. The last album was a little different; the one before was a little different. But I think the general issues that keep coming up are the same. I think this time I decided, okay, I’m gonna talk about Mom, specifically. It was kind of a big thing for me to actually say, alright, I’ll write a song about Mom — by her name, and not hide behind what I usually hid. I figured I gotta do that at least once and might as well do that now. You never know how many albums you’re gonna have, so might as well do it on this one.

I can relate to that. My mom died two years ago after a battle with chronic illness, and the idea of watching someone you love and care about age rapidly or lose their former self in front of you is really poignant. For a lot of people that’s hard to deal with. But there’s also a feeling of hope, redemption, or at least the possibility of a way out on The Agent Intellect. And throughout your work there’s even a sense of humor. How do you reconcile being in a situation as grim as seeing your mother’s health deteriorate while still having to live your life? Is humor a means of coping or moving forward, or do you have other ways of dealing with this struggle?

Humor is just one of the things that you use. It’s a lubricant to keep life moving. It’s a way to talk about things that could be seen as depressing or not funny. When your parents die, you become a member of a club that everyone, if they live long enough, will become a member of. You don’t want to be a member of this club, but everybody is. And you just kind of realize that’s just part of life. You knew it very early on when you were a kid that someday you were going to die. You kind of put it out of your mind for a while, but then as people you love start to die, your own body starts to age, you start to feel like there’s a hill, and you’re reaching the top of it.

Now you can either tear your hair out and start to scream and be depressed about it, and that’s a very acceptable way to deal with it. Part of it is us just trying to deal with that fact and trying to continue to live a life or have experiences that aren’t completely marred with some dark truths about life. So humor helps. Working, whether it’s playing music, or creating art, or working a job, or having a family — these are things that kind of keep your mind off it.

You mention working. Protomartyr has garnered considerable acclaim for their last two albums, but you’re still sort of an everyday man. How has the band’s rise and this international attention affected your day-to-day life?

The favorable attention we’ve got has helped us play shows with people that we’ve never played before. The first three years of existence as a band we played to our friends and a very small group of people in Detroit, which was nice. I loved it. It was a side aspect to our lives. Now, because of the success — it’s not monetary success — but because people know about you, you can actually go to Europe, or you can go anywhere in America, and maybe people will show up.

This year it’s going to be constantly touring to see if all that good press and attention means anything financially, which I just recently had to step away from my job. I’m gonna get back to it when I’m done with it, but that’s six months from now when I get back. The other fellas in the band had to step away from their jobs as well, so it’s a big, big step for us doing that. We’re trying to figure out whether it’s worth it doing that or not. Can the band be your full life, or the main part of your life? I don’t know. But yeah, the good press and people liking the record is great.

One of the first associations with Protomartyr in the press is Detroit, and so many of your songs reference local haunts or city lore. At the same time, your sound can’t be tied to any particular scene here. Do you consider it a burden to represent your hometown or worry that the specificity of your allusions will forever peg you as a “Detroit band” despite your unique style?

No, it’s not a burden at all. If it is a burden, it’s a burden of my own making, because I do make references to Detroit. That’s because I like specificity in my songs, and you write what you know. That’s one way to go about writing a song; you talk about your own life. You want to talk about your environment.

I like Detroit music; I like when people are excited that we’re from Detroit, especially in Europe. People come out specifically to see us because we’re from Detroit. They have no knowledge about us except our name, the date, and that we’re from Detroit. It’d be impossible for me to moan about it if like, all of a sudden it became, oh, I don’t want to talk about Detroit.

The reason we don’t want to talk about Detroit is because we don’t have any answers or anything very interesting to say about it, or profound. A lot of times the questions we get, especially out on the road, are “What is it about Detroit?” And they don’t want the answer, because the answer to Detroit is that there’s bars that you can play, and rent is cheap-ish, and there’s kind of a music scene here, where people are musically literate — they know about the history of bands, and they’re excited to play new things — and people want to have a good time and get drunk.

That’s the thing that helped us in Detroit, but that could apply to tons of places. What they want us to say is, “Oh no, my job working in the comedy club, being sweaty from work really inspires me to make music,” or “The fact that it’s economically depressed makes me want to rail against the man.” I get why they want that. But we’re proud to be from Detroit; I’m proud to be from Detroit.

Your music seems to defy those canned soundbites, as does your band’s name. Or take the opening track of The Agent Intellect, “The Devil in His Youth.” There’s so many religious references on the album. “Pontiac 87” mentions a Papal visit. What role does religion play in your life, and why does it course its way through your music so often?

Well, where I live, I live next to a monastery, and when I was a kid, I worked at the monastery. I was an altar boy. I went to a Catholic grade school; I went to a Catholic high school. Up until I was in my twenties, I probably could count the times on my hands that I missed a Sunday Mass. So I was pretty religious growing up, but it was very nice. I never, you know, fell away from my religion. It was just, kind of, as we get older… You know, I just don’t have the time for it.

The reason why it’s in the songs is because I like that sometimes religion, or at least Christian religion, is something that in America, people have at least a vague understanding about. “Okay, Jesus died.” The allusions that have been used throughout The Bible have been used throughout literature since the beginning of time, or you know, since The Bible was written. So these classic allusions I go for explain things or talk about things that are hard to convey: sin, retribution, all those sorts of things. So I like that sort of stuff; I get fascinated by it.

For “Pontiac 87” I wanted to talk about seeing the Pope and how on one hand it was great to see the Pope, and on the other I could see how petty people could be. You know, churchgoing people can be violent and shove people around. I just like playing with those ideas.

Switching gears from the sacred to the profane, and from your most recent album to how Protomartyr first began: Butt Babies. How did you stumble upon them [the duo of guitarist Greg Ahee and drummer Alex Leonard], and how did you grow into what Protomartyr is today?

Well the reason that they had that name is that they didn’t want to take themselves too seriously, which is a disease that runs through any sort of art, especially with bands and in music. A lot of people use it as an excuse to be self-important or take themselves way too seriously. “I’m creative.” So that’s why they were called Butt Babies, and that’s what I liked about them.

They had a good work ethic, where they would try to come up with a song when they were together practicing. I mean, they would call it fucking around, but it wasn’t fucking around. They had a goal where they would do a song a day. And I liked the fact that they didn’t take themselves too seriously, and they were artistic without being pretentious about it.

Pretension can be good, and I think David Bowie is the perfect example of it, and he made it seem possible. So I was attracted to them as a band because they were called the Butt Babies, but they made interesting music. I like people that don’t take themselves too seriously. I wanted to be less serious about myself.

You’re the frontman of a band in which the rest of the members are roughly a decade younger. How does that dynamic play out?

They don’t see me as anything but another guy in the band. Maybe outside that, you know, they definitely know I’m old. Older. But it really doesn’t come into play much. It’s just that… It’s like it’s one of the things where I’m different than they are, but it’s not like they’re all coming from the same experiences, so it’s all what we bring to the table. I bring a little more life to the table — aches and pains — but no, it really has nothing to do with anything.

Except we did mostly had to talk about it because other people were talking to us about it as if, “This looks like a dad taking his kids out as a band,” or “A weird drunk uncle and his nephews” or something. So we really had to talk about that, but it wasn’t very odd because, you know, I had the same job Greg had at the time, and I wasn’t like his boss. I’m not the boss of anybody in the band, so it really isn’t much of an issue.

The first time I saw Protomartyr perform, I remember thinking — before the band even played a note — that each member seemed to belong to a different subcultural tribe. But when the music started, you sounded so taut and of a piece. What is it like when you’re first learning a song, rehearsing, or performing live? Is there some magic formula to arrive at that unity? Because visually, you’re so disparate, yet sonically, you’re so unified.

There’s no set Protomartyr way of doing things as far as coming up with songs — it changes. And I think it’s mostly because we have never got to a point where we’re like, worried about stage presentation. We kind of know where our roles are in the band, so you’re not going to witness a lot of “You should do this; you should do that.” When we first started the band, we probably wanted to look cooler than we do. I know we wished all looked a certain way. There’s some great bands that all have a very unified visual look, but I realized pretty early on that that’s what I hate a lot.

We get lumped in with post-punk quite a bit, and I hate that a lot of modern post-punk bands all look like they came out of a, you know, emo boys’ fashion magazine or something. Your music is dark, so you must look dark. I get why that’s important, but it’s not really been a thing to us. Should Scotty get a haircut? No. It’s one of those things that means nothing, but it’s all about the music. At the end of the day, it’s about what you put out. It’s one of those lame things that bands say, but for us, it’s not about how we look, it’s not about our political opinions, it’s about the music.

Post-punk is a genre that Protomartyr are often associated with, but what bands or artists are you influenced by?

Well, there’s a couple ways to do it. There’s people that I admire for how they went through their career or what they’re doing with music. You know, I admire them, but I would never want to sound like them, or I would never want to ape them. I get asked this question all the time, but I don’t know how influence works.

I think one of the profound things about the David Bowie thing that I didn’t necessarily feel myself is that he made it possible for me to feel good to feel normal. And you know, I think that’s how influence works. Maybe an artist doesn’t influence you directly, but they maybe make you feel that what they’re doing is okay or commonplace, so now I can do it too.

I like The Fall, but the rest of the band are not particularly big fans of them. I’m still confused about what exactly post-punk is. Like I said, I like The Fall; I like Magazine. People always compare us to Joy Division. Really, honestly, I never listened to much Joy Division. I never really listened to much Interpol or modern post-punk. I guess I don’t know what exactly they mean by that genre except for — I don’t know — slightly gloomy, slowed-down punk?

With music, you don’t know what’s going to influence you. You gotta be open to it, without aping it too much. Actually when writing lyrics for songs, I try not to listen to too much music or read too many poems. I don’t want that leaking in and corrupting it. That’s not to say I don’t steal things specifically, but I don’t go in there with a mission that I want this line or I want this phrase. I don’t know how influence works. I just let it happen.

Protomartyr have been going pretty much nonstop the last two years. You didn’t take a break between Under Color of Official Right and The Agent Intellect. You just came off one leg of a tour and are about to embark on another one. Is there anything that you’re looking to do differently this time around?

The main thing is that when we come back from this tour, which is a very long tour, a lot of us won’t have jobs. So then it becomes how do you fill that time. Whereas before we could just write music on the road, I don’t think we can, just because we’ll be touring so much. But we do know how to tour now. We’re getting pretty good at it. It’s when we get back that it’s going to be like maybe we need a practice space now, because Scotty’s basement has worked for us in the past, but it’s like, well, we’re not going to have jobs, so we’re going to want to work on stuff more.

That’s going to be a change. Just getting used to being a band that’s “doing it full-time” is gonna be a change. How it affects the music I don’t know. But I’m looking forward to getting back from all of this touring. It’ll be very interesting to see what kind of music we can make after all of this. I don’t think we’ll be burned out. It’s weird. I usually think we’re at our best coming back from a tour.

Any particular place that you’re looking forward to touring?

I’m looking forward to Ireland. I’ve never been there. I’m excited about Poland. The first time we went to Poland was a great experience. Everywhere. You’re excited anywhere you’re going, because it’s someplace new.

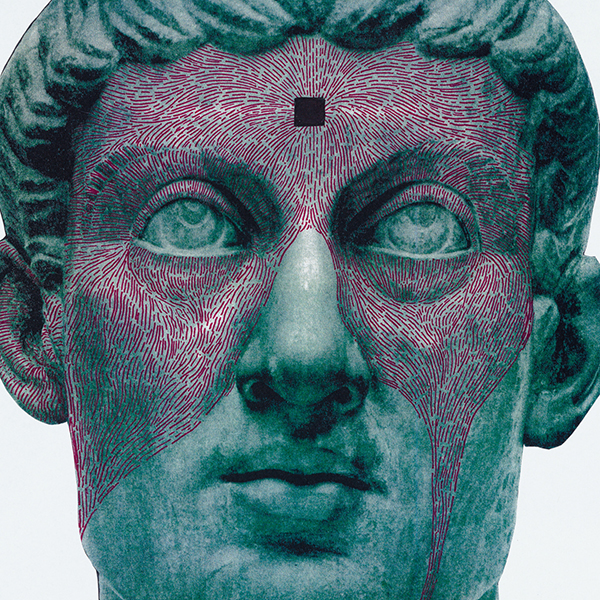

Press photos of Protomartyr by Zak Bratto and provided courtesy of Pitch Perfect PR.