Death is Detroit-rock’s greatest underdog story.

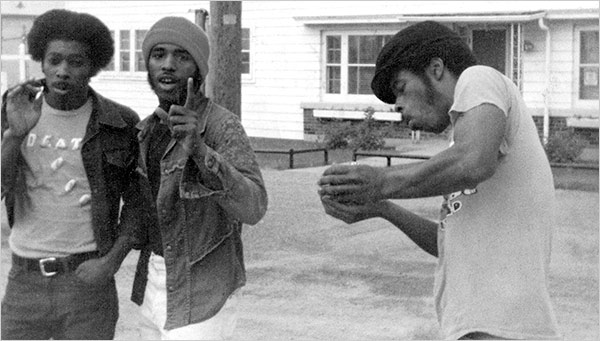

Founded in 1971 by Detroit-native brothers David, Dannis and Bobby Hackney, Death’s music is the product of classic rock influences, stubborn determination and a well-documented and triumphant rediscovery. The band’s debut album, For the Whole World to See, was recorded in 1974, yet remained somewhat unheard until its highly-acclaimed release in 2009 via Drag City.

Death began as more than just a musical project. It began as a concept. Death represents the supreme triangular balance between mind, body and spirit. The band’s sound, name and energy proved too progressive for many in the music industry 0f the 1970s. After a record deal gone-bad (an offer which involved Clive Davis, and a request for the band to change its name) – Death faded into obscurity.

Bobby and Dannis Hackney relocated to Vermont and began a reggae group called Lambsbread in 1983. Death’s stubborn leader David Hackney would eventually succumb to lung cancer in 2000, but only after bestowing upon his brothers the master tapes of Death’s early recordings. These original recordings remained untouched in a Detroit attic for nearly a decade.

Lambsbread was looking forward to it’s latest album release during the late 2000’s, but the project was eventually put on hold due to an amazing discovery. Death’s music had become a focus of music collectors, underground clubs and punk rock historians. Original pressings of Death’s recordings were selling online for nearly $1000.

After becoming aware of Death’s underground popularity (with help from the Internet’s rare vinyl aficionados) the two surviving members of Death planned the return of one of rock music’s greatest untold stories. Recruiting their reggae band’s current-band mate Bobbie Duncan, Death organized the group’s triumphant return to rock-n’-roll.

Death’s story has since been immortalized in a 2012 Drafthouse Films documentary titled, A Band Called Death (currently available on Netflix’s online streaming service with a Rotten Tomatoes rating of 96 percent).

Death, which is anticipating the release of its archival collection (Death III) and a new autobiography, recently spoke with Detroit Music Magazine regarding the band’s infamous story, Detroit’s music history and the future of David Hackney’s musical vision.

______________________________________________________________________________

You just returned home from Paris. What is the European take on Death?

BH: We were very, very well-received. You know, it was a sold-out show. A place right outside of Paris – it was great. It was really nice.

Detroit artists get a lot of respect in Europe. Why do Detroit artists seem to stand out to European audiences?

BH: You know, Detroit makes good music. A lot of music that the United States does around the world started in Detroit, you know?

What makes Detroit’s music scene so special?

BH: In Detroit, when you play music, anything can happen. And I’m sure anything can happen in a lot of other places, but in Detroit – it’s just all around you. You got Motown, but you also got Detroit rock… you got a lot of great bands, great acts and great radio stations. Yeah, that’s the Detroit we’re talking about man.

Well starting out in Detroit… you and your brothers were inspired at a young age by watching The Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show. You know, this year marks the 50th anniversary of that broadcast.

BH: Well, we were fortunate enough to watch the real thing – thanks to our dad. It’s funny. I was only eight-years-old at the time. You know, there were only three channels at the time: CBS, NBC and CBC. I gotta tell you man, everyone was always in-tune to the big event that was happening. My dad, he was kind of like that. He made sure we sat down and watched that. He told us it was going to be history… that history was in the process of being made that weekend, because America had never seen nothing like that. And it was true.

Exactly how different was Death’s sound at the time of the band’s beginning?

DH: Well, it was a sound that we were working on, but we didn’t really know, or appreciate, the uniqueness of it until after it was recorded. Writing the songs… I mean, because things kind of happened fast for us in those days, it was like we had finally found what we wanted to play, so Dave and Bob knew what kinds of songs we wanted to play. You know, once we found our identity in music.

Well, your album titled For the Whole World to See was recorded in 1974/1975, but released in 2009. How has the meaning of the title of that record changed over these years?

DH: Well after all these years – yes. It took a whole generation to become accepted. In the 70s Death was scary. It was a scary name. But in the 90s – it wasn’t so scary, you know what I mean? This music was scary in the 70s, but in the 90s it wasn’t so scary to the younger people of that era. So, that’s what I mean when I say Death had to wait a whole generation before the music got appreciated. So, I mean, it felt good to go from obscurity to notoriety. You know what I mean? Back then it felt like everybody and his mother hated us. We couldn’t even practice without the cops being called, or the doors being slammed or – you know… it was quite a fight to maintain identity. Even right there in the neighborhood. So, when you ask how it feels man – it feels really good. To go from everybody hating you… [laughs] to everybody loving you. It took, what? 30-some years.

BH: You know it really hasn’t changed. That was David’s title. He titled the album For the Whole World to See. You know, it’s ironic, because his music is being recognized all over the world and it’s like his words are coming true. We have yet to play a lot of places, but you know, David’s idea of a world tour was to play every place in the world. Even once. You only had to play it once. Every town and every city in the world. That’s what he said a real world tour is, you know. So, that’s really what our goal is… that’s what Death’s goal is.

What was the initial reaction when you found out that people like Ben Blackwell were paying almost $1000 for these original pressings of Death’s material?

BH: Well, it was crazy man. You know, we really have to thank those record collectors, because it was really the record collectors that put things out there. Got things going. They let people know that they had found something really rare. Like Don [Davis] said in the movie: if you would have met us back then, we would have given you one for free. [laughs] And it was true. [laughs]

Well not anymore. [laughs]

BH: But we were looking to get airplay. We were just trying to get our music heard, man. Once again, we have to thank those record collectors. We just have to be thankful.

Well, For the Whole World to See was recorded at United Sounds Systems in Detroit. There has been a debate going on in Detroit regarding the I-94 highway expansion project, which is threatening the United Sound Systems building. How important of a landmark is United Sounds to Detroit’s music history?

BH: To Death… we signed that petition. That’s how important it is to us. We signed that petition. We hope that the building will be deemed a historic landmark, because it is. You’re talking about the studio where Berry Gordy did his first demo recording with Jackie Wilson. You’re talking about the studio where the Rolling Stones recorded. Rare Earth. The Who. The Funkadelic. Aretha Franklin. Marvin Gaye. Every Motown artist… Miles Davis. The list just goes on and on. And I have yet to mention the hits that were made while we were recording there during the 70s. It is a very historic building.

It seems ridiculous that Detroit is even having this debate.

BH: Exactly. We are right there with you.

Well, there was fantastic documentary made about Death. It was quite the emotional ride. I thought it was just going to be about rock and the history of the music. When I was finished – you know, I was inspired. It gave a great look at your brother David, the former leader of Death, but it also gave viewers a lot to walk away with. What did Death gain from the experience? What did you all learn from the retelling of the band’s history?

BH: Well it was closure on one end. On the other end, it’s not closure, because all three of us here would love to have David with us. That’s the burden that we carry. I speak this also for Bobbie Duncan as well. All three of us would love to have David with us. It’s closure to see the music get notoriety. It’s closure to see people understand the concept of Death, and talk about it in the light they talk about it today.

DH: But the real work has just begun.

BH: It’s not closure for what we have to do and what’s ahead.

As far as your involvement with Death, Bobbie Duncan – what is your perspective on all of this? As not being a founding member of the band, what was it like for you during this examination of the band’s history?

BD: Well, it’s been a journey. I’ll tell you, I didn’t get it at first. [laughs] We were doing reggae man. I was an active musician and when the Death thing came around. We were already doing stuff and we had an album, a reggae album, that we were already pushing. One Thursday night at rehearsal, Bob Hackney brought down a CD, and a story along with it. Evidently, Bobby and Dannis had known about the resurgence for probably about a month or so before I even knew about it. They had reservations on putting it on the table for me. You know, they didn’t know if I was going to accept it. When he brought it down, as the musician that I am, I was like, ‘I’m game for anything.’ You know? It’s kind of weird that the name was Death, but once I heard the track I was all over it man. To this day, one of my favorite songs is still “Prisoner.” But I didn’t get it at first. I didn’t know the story. I had no idea how deep it really went. Actually, we went on our first mini tour, in Detroit – that’s when we started getting into it man. It was like, ‘Wow, this is more than just playing a gig.’ Because I’ve been doing this since I was 12. You put a record in front of me and I learn it. I’m a musician, you know? But, once I got the whole story I actually felt tears in my eyes. This guy [David] had a concept. These brothers had a dream, man. If I were an A&R guy back then, I would of said, ‘To heck with the name man. Put the music out.’ What’s the problem? Every time I get on stage with them I’m having a lot of fun.

Death has had some really cool placements in the last few years. One of these was on the show How I Met Your Mother. How is your selection for where your music is used different from how it may have been had Death taken off in 1975?

BH: Yeah, we probably would have been a little bit more… discerning back then. I mean, you never heard any of the artists’ music on television back then, because you could come off as not being too cool back then. I couldn’t imagine, back then, The Who or Ted Nugent’s music being played while a bag of potato chips went dancing over a hill. [laughs] You just didn’t see that back then! [laughs] We never thought of that! And artists wouldn’t allow that.

DH: It was uncool.

Well, a really cool placement from Death was within Ishod Wair’s skateboard video for Nike Skateboarding: The SB Chronicles 2. He didn’t just play part of it – “Politicians in my Eyes” is the entire video’s soundtrack. Now, Ishod Wair is a professional skateboarder. He’s also black. In your opinion, how have you seen punk/rock, which I think many people associate with skateboarding culture, how has this culture changed in regards to racial boundaries and norms?

BH: I gotta tell you, my kids… you see my kids in the movie – they grew up in the skateboarding culture. I mean, they took to skateboarding. My oldest son Bobby took to skateboarding when he was about 12-years-old. He never looked back. He was turning me on to a lot of different bands. I’m talking bands like Henry Rollins, Black Flag, The Dead Kennedys, Bad Brains… he was turning me on to those kind of bands, because those were the kind of bands that were part of the skateboarding culture, you know? That kind of culture has become synonymous with rock-n’-roll, and especially hardcore and punk music.

BD: First of all, you know, when Bob, Dannis and I came up, we only had AM radio. Whatever was a hit, they played on the radio. You had The Beatles and then you had Motown, then you had James Brown and you had The Rolling Stones. You didn’t have to turn the dial to hear rock-n’-roll. We grew up hearing everything. I believe that within the next few years, those lines are not going to be there. You young folks are getting tired of all this. It’s just going to be like… music. The way it should be. It’s not going to be black music, latin music, white music… you know? It’s just music. If you want to dance to this beat or that beat – it’s what you feel. You can even tell by the way kids are dressing these days. Nobody’s really dressing black or white. It’s crossing those lines man. The Internet has knocked those walls down, I believe. Kids just hear what they want to hear. What do you think Bob?

BH: Definitely. We see it at all of our shows.

BD: That’s right.

BH: The wonderful thing about a Death show is that we play to each and every culture, and every color in the world. It’s amazing. At shows people approach us and tell us how much they appreciate the music. We definitely do see those racial barriers braking down. It’s the progression of the world, man. That’s the world that we’re living in now.